Romeo and JulietA tragedy by William Shakespeare, arranged in two acts and twenty-three scenes by Katharine Cornell. Opened at the Erlanger Theatre, Buffalo, New York, November 29, 1933, the first performance of Cornell's seven month transcontinental tour. The play was performed 39 times during the tour. Produced by Katharine Cornell, staged by Guthrie McClintic, settings and costumes designed by Woodman Thompson, dances arranged by Martha Graham, fencing arranged by Georges Santelli. music by Paul Nordoff. Miss Cornell's and Mr. Rathbone's costumes by Helene Pons Studio. The other men's costumes and uniforms by Eaves Costume Co., Inc.; the other ladies' costumes by Mme. Freisinger. Production built by J. M. Nolan Construction Co. and painted by Robert Bergman Studio. Electrical equipment by Century Lighting Company. Shoes by Georges. Wigs by A. Barris. Draperies by I. Weiss & Sons.

Romeo and Juliet was one of three plays that Katharine Cornell and her company performed during a transcontinental tour from November 1933 through June 1934. Details of the tour can be found here: Cornell Tour 1933-1934 . The story of the star-crossed lovers Romeo and Juliet is well-known. Very briefly, the Montagues and Capulets, two wealthy families in the city of Verona, are constantly fighting one another. Young Romeo Montague and his friends Mercutio and Benvolio crash a masked ball at the Capulet house. At the ball Romeo meets Capulet's daughter Juliet, and they fall in love instantly. After the party, Romeo sneaks into the Capulet's garden and calls to Juliet, who is on the balcony of her bedroom. They declare their love for one another and plan to marry. With the help of Friar Laurence, the two lovers marry in secret. Later, when Romeo is celebrating with Mercutio and Benvolio, Juliet's cousin Tybalt picks a fight with them, and kills Mercutio. Enraged, Romeo then kills Tybalt. The prince punishes Romeo by banishing him from Verona. Romeo and Juliet spend the night together before he flees to Mantua. Unaware that Juliet has married Romeo, her father Capulet arranges for her to marry Paris, kinsman to the Prince, in just three days' time. Desperate to avoid a forced marriage to Paris and be reunited with Romeo, Juliet seeks the counsel of Friar Laurence. He suggests a plot in which Juliet fakes her death, and when she awakes from her deathlike slumber, her beloved Romeo will be there, and they can live happily ever after. Sounds like a great plan, but Romeo doesn't get the message from the Friar about Juliet's fake death. He hears only that Juliet has died. Seeing her apparently lifeless body in the tomb, Romeo decides that he cannot live without her; he kills himself. When Juliet then awakes, instead of being joyfully reunited with Romeo, she sees his dead body. She likewise kills herself. In the face of this double tragedy, the Capulet and Montague families vow to end their feud.

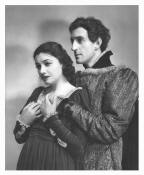

Juliet is the first Shakespearian role to be acted by Katharine Cornell. She said in interview with The Buffalo News (November 27, 1933), "My decision to do Shakespeare was based on the assumption that an actress to whom the theater has been kind has an added responsibility to the theater—especially in embarking on a 15,000-mile tour. She must do the best things when she has grown up to them. I only hope I have. There is no reason why Shakespeare should be approached with such an overweening awe as he has been in the past. We have undertaken Romeo and Juliet with no preconceived notions. It really is the best melodrama in the world—swell theater." Once Katharine Cornell decided she'd like to try playing Juliet, she and her husband, Guthrie McClintic, began to study the play, to plan their staging and acting exactly as they would had it been any other good play newly come into their hands. After months of preparation, when their ideas were crystalized, they devoted weeks of study to all records available of other productions of Romeo and Juliet. They read all the existing stage versions of the tragedy, accounts of the famous Juliets from the past. Neither Katharine Cornell nor Guthrie McClintic had seen the play since they were children, and thus their minds were unhampered by preconceived precepts and concepts. What they read that seemed to them vital and fitting for their scheme they incorporated in their presentation. They were determined that Shakespeare must be a living man speaking to audiences today exactly as he spoke to them 300 years earlier. In an interview with Wood Soanes of the Oakland Tribune (February 4, 1934), Cornell said, "We felt that we should take no liberties with Shakespeare. We decided that here was a truly exciting play with one of the loveliest finales ever written: a play that seemed to divide itself without our direction into two definite parts—one a beautiful romantic comedy; the other a moving romantic drama. I believe we have been successful." In no sense have they "modernized" Shakespeare. They have dressed the play in the period of the Italian renaissance and provided 20 elaborate settings of pictorial representation. What they have done, however, is to equip their production with every modern stage technical means so that one scene may be changed to the following one with a minimum of intermission, thus borrowing form the movie or, rather, restoring to Shakespeare the continuity of the Elizabethan stage. With only one interval, the tragedy progresses without halt, and the spell and the sweep of the drama is unbroken. In Romeo and Juliet, Cornell stressed the play rather than any individual role. The twenty scenes, elaborate in the period of the Italian Renaissance, are changed one to another with almost movie rapidity. There is only one intermission, so the sweep and spell of the tragedy is not disrupted. Basil Rathbone shared his opinion in an interview with The Charlotte Observer (April 8, 1934), saying that Romeo is one of the most difficult of all Shakespearian characters to interpret. "Shakespeare gives Romeo practically nothing to do, and, until the scene in which he learns of Juliet's death, he isn't even a man—just a boy, sick with calf-love! I'm afraid Romeo was pretty much of a sap, according to modern day standards. He was the dreamer, the poet, who died for his love. He was never the virile he-man type—and the world has little tolerance for him today!"

In an interview with the St. Louis Globe-Democrat (March 7, 1934), Basil Rathbone said, "Shakespeare is the best training an actor can have. Young girls and men tell me that Romeo and Juliet is 'silly,' that no one acts like that in life. It is true, no one can speak as Shakespeare made his people speak, but people do feel and experience what the great poet put into his men and women. Romeo may seem to the modern youth a moon-sick lad, but Romeo died for love of Juliet. I wonder how many of the glib young fellows who laugh at Romeo would do that for the young ladies they profess to admire. "We don't modernize Shakespeare. It isn't necessary. He is curiously enough always modern, always ahead of the times. The problem of the actor today is to meet Shakespeare on his own ground, not as a must museum relic. Then Shakespeare comes into his own. Miss Cornell and Mr. McClintic, it seems to me, have the right approach. They haven't been afraid of him or of the ghost of other generations. 'Here' they apparently said, 'is a grand play. Let's do it!' And they went ahead and gave it all the benefit of modern stage technic, made it real and alive, made the passion of these two youths tragically actual, as though Romeo and Juliet at first sight did feel the flame of love and threw the world aside."

The Cornell company's transcontinental tour opened with a performance of Romeo and Juliet in Buffalo, New York on November 29, 1933. She used 19 students from the University of Buffalo in the play's mob scenes. "Katharine Cornell made her Shakespearean debut in Romeo and Juliet. ... A hometown audience accorded her a storm of applause after showing her and her associates hearty appreciation throughout the twenty scenes of the production, colorful and capably directed. ... Rather an intellectual player than physical, it seemed last night that Basil Rathbone was hardly a happy choice for Romeo. A good actor, he none the less is much more at home in drawing-room drama than in heavy tragedy of the Shakespearean category." —W. E. J. Martin, Buffalo Courier Express, November 30, 1933 "Basil Rathbone, the Romeo of the production, is a player of much Shakespearean experience in previous years. He is a handsome and romantic figure with flowing cape, doublet and hose. Generally speaking, one gets t4he impression that he is a decorous, soft-spoken Romeo whose furores of passion and impetuosity are just a little difficult to believe." Rollin Palmer, The Buffalo News, December 1, 1933

"Mr. Rathbone’s Romeo is no less the youth consumed by his last love. As with all youth, the last love but one becomes as nothing. Though he had developed the same symptoms the week before over the beauty of another, the jibes of his companions are futile either in dispelling his gloom or restoring him to objectivity. It would be unfair to Mr. Rathbone to discuss the performance of Miss Cornell separately because it is predominantly their work together which is superb. To the conception of Miss Cornell—that Juliet is ripe woman, not mooning child—Mr. Rathbone gives perfect complement. He plays with the depth demanded by such a conception. . . . My belief is that to act Shakespeare well is to act as one would act to play anything well. This means, if it means anything, to act the thoughts and not the words of Shakespeare. Which seems to be exactly what the Cornell troupe accomplished last night at the Davidson. The accomplishment did not sacrifice melodic beauties but reduced them to their proper proportion." —Harriet Pettibone Clinton, The Milwaukee Leader, December 9, 1933 Katharine Cornell's Romeo, Basil Rathbone, is a player of much Shakespearean experience, as handsome as the word 'Romeo' implies, quite as romantic as doublets, hose and flowing velvet capes can make him, and quite as full of the poetic passions as any Montague can be. The role of Romeo, owing to the recent restrained fashion in wooing, is quite the hardest of the well known Shakespearean parts to sell to a modern audience. But Mr. Rathbone sells it. He has his big moment in Friar Laurence’s cell when the news is brought to him that he has been banished from Verona for skewering Juliet’s obnoxious cousin Tybalt." —Irving Ramsdell, Milwaukee Sentinel, December 9, 1933 "Basil Rathbone is the present Romeo. His interpretation, also, is a departure from the staple. He, too, is less concerned with cadences and sonorities and nicely adjusted accents than with presenting a luckless young man in the throes of passionate devotion. Mr. Rathbone does not ignore the classic rules to swagger and eloquence and does not cheat the eye of its supposed delight in elegance of costume, but he offers a Romeo with blood as well as phrases stored within him." —Richard S. Davis, The Milwaukee Journal, December 9, 1933 "The Romeo Mr. Rathbone gives us is a studied, invigorating and masterful characterization. Performances of other members of the company vary from competent to less than passable. Pronouncement of some of the most beautiful poetic passages in the play are rather badly mangled." —Merle Potter, The Minneapolis Journal, December 16, 1933

"Basil Rathbone's Romeo is vital, handsome and believable. He plays it strongly and skillfully, with full appreciation of the beauty and meaning of each line. He is a headstrong, impetuous Romeo to whom life without his loved one is convincingly impossible." —Fred M. White, The Oregonian, January 6, 1934 "Rathbone's Romeo was unsteady last night, not in rendition so much as interpretation. He seemed to take the keynote of the role from the craven scene in Friar Laurence's cell when he learns of his banishment. To his credit it must be said that he sustained the idea although its value is debatable. His articulation was indifferent, too, in many scenes although occasionally one forgot his limitations in the skill of his interpretation of certain scenes." —Wood Soanes, Oakland Tribune, January 9, 1934 "Basil Rathbone made a Romeo of dignity, reading his lines with fine feeling, but still never quite matching Miss Cornell's bewitching fervor. His performance, excellent though it was, seemed just a trifle too academic. And seeing an academician make love is like concluding Tristan with a Liebestod by Stravinsky. But then Mr. Rathbone obviously had a cold, that that, I'm told, is as potent foe of Eros as is erudition." —Lloyd S. Thompson, The San Francisco Examiner, January 10, 1934 Regarding the performance at the Biltmore in Los Angeles, Variety (January 23, 1934) reported, "Basil Rathbone as Romeo gave an excellent performance He has lost a great deal of the stiffness that was always his fault."

"Young, supple, vibrant, Miss Cornell presented a loving and high-spirited girl entranced both by her lover and her first love. Tender, throwing herself into the connivings of the Montague-Capulet feuds, she brought vivid and convincing beauty and a fine dramatic fervor to the role. Basil Rathbone, as the romantic Romeo, provided a splendid foil to the work of the star, who shared graciously the many scenes in which his part is dominant. With all that lithe activity, which denoted the young aristocrat of Padua, Mr. Rathbone was equally realistic as the poetic lover and the fiery devotee of family honor." —Florence Lawrence, Los Angeles Examiner, January 23, 1934 "Basil Rathbone gives a sensitive performance as Romeo." —Harrison Carroll, Los Angeles Evening Herald and Express, January 23, 1934 George Lewis of the Los Angeles Evening Post-Record (January 23, 1934) wrote, "At the end of the first act, I was pretty sure Will Shakespeare, when he created Juliet had Katharine Cornell in mind. She is the dark lady of the sonnets. So gracefully does she slip into the role that the audience who came to see Katharine Cornell, left the theater having seen Juliet. With that fleeting, exquisite expression and those graceful, slow movements of the hands, Miss Cornell has the audience captured and begging for more captures. Basil Rathbone did a capable enough job being, however, a trifle too heroic even for Romeo. The lines are spoken with remarkable clarity." Norma Shearer (Basil's co-star in The Last of Mrs. Cheyney) and her husband Irving Thalberg saw the performance in Los Angeles. On January 23, Norma sent Basil a telegram: "DEAR BASIL IRVING AND I WANT TO TELL YOU HOW REALLY FINE YOUR PERFORMANCE WAS LAST NIGHT YOU WERE A JOY TO THE EYE AND EAR WHAT A PERFECT ROMEO LOVE TO YOU AND OUIDA."

"Rathbone has abandoned the posings that marred his Romeo and hallmarked it for the school in which he first learned Shakespeare. Now he gives full tone to the lines but is less conscious of them. He is a brash young man deeply in love with an attractive young girl, and when he rails at the ill fate that pursues them it is honest and juvenile rage." —Wood Soanes, Oakland Tribune, February 6, 1934 Miss Cornell's Juliet ranks with the finest interpretations in the field of Shakespeare heroines. Above all, her Juliet is convincing. It reached the hearts of the audience; and that is the test of the theater. ... No one knows better than Miss Cornell that her own performance was made possible by the excellent acting of her co-star Basil Rathbone, in the role of Romeo. Their first balcony scene was the outstanding bit of work during the evening—perhaps one of the finest ever given. In this Basil Rathbone rose to heights and shared honors with Miss Cornell." —B. Roland Lewis, Deseret News, Salt Lake City, February 10, 1934 "Basil Rathbone, who is no stranger to Shakespearean roles, contributes a handsome, sensitive Romeo to the familiar cast of characters. He makes of Romeo a likable, ardent lover who has little of the stilted formality so commonly found in Shakespeare characters." —Fred Speers, The Denver Post, February 15, 1934 "Rathbone, formerly a leading man on the screen, did not enunciate as clearly as a Shakespearean text demands, nor were his postures always suitable to the action. Yet Rathbone made Romeo a viril Montague, a handsome lover and a brave husband." —Robert Randol, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, February 20, 1934

"The Romeo of the Cornell Shakespeare as played by Basil Rathbone is not the complete mooncalf he has so often appeared. There is the very real feeling that he is the sort of young man who would die for his love of a fair Juliet." —Lecta Rider, The Houston Chronicle, February 25, 1934 "Basil Rathbone acquitted himself admirably as Romeo. He made of Romeo more than a love sick boy—he gave virility to a role which is predominantly naive, dreaming and poetic." —Bess Whitehead Scott, Houston Post, February 25, 1934 "In the list of noted actors whose fame rests entirely on Shakespearean characterizations it is doubtful if there is one who becomes the role of Romeo as handsomely as versatile Basil Rathbone. His presence is a pleasure to see every moment and his reading of the lines and his acting as this unlucky lover seem complete. He is, indeed, an ideal teammate for Miss Cornell." —Lowell Lawrance, Kansas City Journal, March 6, 1934 Basil Rathbone of stage and photoplay fame, is a tall and manly Romeo, if, withal, a Romeo who seems to become overly melancholy about his lot too early in the play, overly afraid that he and Juliet are not going to find the happiness that should be theirs and that they desire so dearly." —The Kansas City Times, March 6, 1934

"Mr. Rathbone, the very handsome young Romeo, seems to be wedded to an English method of delivery that harks back to tradition." —Homer Bassford, The St. Louis Star and Times, March 20, 1934 "Although always in complete harmony with Miss Cornell, the dividing line in Rathbone's interpretation is slightly distinct. the erstwhile featured player in Hollywood motion pictures is entirely up to the demands of the part at all times, is a wholly adequate Romeo." —Herbert L. Monk, St. Louis Globe-Democrat, March 20, 1934 "Basil Rathbone, as Romeo, holds more closely to the older demands of the followers of the Bard. A striking figure and an artist to his finger tips, none of the poetry of the play escapes his rendition and he easily shares, with the star, the honors of the performance which, as a fact, the part demands." —H. H. Niemeyer, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 20, 1934 "Mr. Rathbone gives substance and eloquence to the essential spirit of the Elizabethan hero. His Romeo is full of hardihood and manliness. He has impetuosity and dash, is ready with his tongue, ready with a sword. He feels a real exuberance that goes out to meet experience. He is sportive and violent and gracious, and all of these varied characteristics are woven together into an emotional pattern that is fine and moving." —undated and unidentified newspaper clipping Cincinnati was the last city on the tour in which the company played Romeo and Juliet. Due to the complicated set up, they couldn't manage it in the "one night stand" cities.

Cornell et al. found audiences on the tour more enthusiastic than New York playgoers. "At Romeo and Juliet, for instance, they would applaud after every scene, without even waiting for the intermission. It was as if they were saying, 'We want you to know, right now, that we like it.' . . . If New York audiences seem less demonstrative than some of those I've played to this season, it's not from any lack of appreciation. It's just that the theatre is a more usual thing with them. Then, too, they know the cast won't come out and bow until the end of the play, and that rather discourages applause. On the road people are not so familiar with this custom." (New York Herald Tribune, June 17, 1934)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||