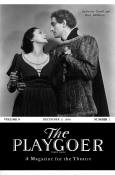

Romeo and JulietA tragedy by William Shakespeare, arranged in two acts and twenty-three scenes by Katharine Cornell. Opened at the Martin Beck Theatre, New York City, December 20, 1934, and closed on February 23, 1935, after 77 performances. Produced by Katharine Cornell, staged by Guthrie McClintic, settings by Jo Mielziner, dance direction by Martha Graham, music by Paul Nordoff.

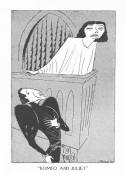

The story of the star-crossed lovers Romeo and Juliet is well-known. Very briefly, the Montagues and Capulets, two wealthy families in the city of Verona, are constantly fighting one another. Young Romeo Montague and his friends Mercutio and Benvolio crash a masked ball at the Capulet house. At the ball Romeo meets Capulet's daughter Juliet, and they fall in love instantly. After the party, Romeo sneaks into the Capulet's garden and calls to Juliet, who is on the balcony of her bedroom. They declare their love for one another and plan to marry. With the help of Friar Laurence, the two lovers marry in secret. Later, when Romeo is celebrating with Mercutio and Benvolio, Juliet's cousin Tybalt picks a fight with them, and kills Mercutio. Enraged, Romeo then kills Tybalt. The prince punishes Romeo by banishing him from Verona. Romeo and Juliet spend the night together before he flees to Mantua. Unaware that Juliet has married Romeo, her father Capulet arranges for her to marry Paris, kinsman to the Prince, in just three days' time. Desperate to avoid a forced marriage to Paris and be reunited with Romeo, Juliet seeks the counsel of Friar Laurence. He suggests a plot in which Juliet fakes her death, and when she awakes from her deathlike slumber, her beloved Romeo will be there, and they can live happily ever after. Sounds like a great plan, but Romeo doesn't get the message from the Friar about Juliet's fake death. He hears only that Juliet has died. Seeing her apparently lifeless body in the tomb, Romeo decides that he cannot live without her; he kills himself. When Juliet then awakes, instead of being joyfully reunited with Romeo, she sees his dead body. She likewise kills herself. In the face of this double tragedy, the Capulet and Montague families vow to end their feud.

Cornell's Romeo and Juliet (along with The Barretts of Wimpole Street and Candida) was also performed during a seven-month U.S.A. tour from November 1933 through June 1934. Click here to read about the tour. On June 28, after the tour had ended, Katharine Cornell and her husband Guthrie McClintic sailed for Europe, for a vacation in Majorca, the Riviera, Geneva, and the Bavarian Alps. Rathbone had a very different sort of "vacation": He had his tonsils removed, and then retreated to a little cottage on a golf course at Great Neck, Long Island. In August MGM agents came looking for Rathbone to offer him the part of Murdstone in David Copperfield; they tracked him down on a New England farm. The farm was likely the home of Rathbone's friend, fellow-actor and singer Mike Bartlett. Rathbone's beloved dog Moritz had died in May and was buried on the Bartlett property in Oxford, Massachusetts.* Rathbone traveled to Hollywood to arrive by September 17, when filming for David Copperfield began. Katharine Cornell had left her dog Flush in Rathbone's care while she was vacationing in Europe, so Flush got to go to Hollywood too! Rathbone (and Flush) returned to New York in late October, in time to start rehearsals for Romeo and Juliet on November 8, 1934. Before opening on Broadway, Romeo and Juliet was performed in the

following four cities:

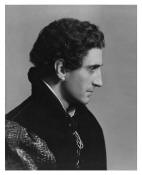

Most of the reviewers in these cities praised Rathbone's performance: "Basil Rathbone's Romeo was vigorous, well turned, and growing in favor as the evening progressed." —Len G. Shaw, Detroit Free Press, December 4, 1934 "Mr. Rathbone in voice, figure and ardor is never less than magnificent. His diction is music, his love-making fiery." —Annie Oakley, The Windsor Star, December 4, 1934 "Basil Rathbone is the handsome romanticist with which legends of the past have endowed their Romeos, a virile lover, a persuasive wooer and a fine tragedian. His is an accurate performance, intelligent, sensitive and commanding." —Harold W. Cohen, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, December 14, 1934 "Basil Rathbone makes music of words. ... He struck at the beginning of the play, and maintained throughout the play, a restraint which tended to mute his performance. At all times distinguished, and marked by a flawless enunciation and highly intelligent reading, his Romeo did not BURN. He looked very handsome. He 'behaved' almost too nicely. In his scenes with the ribald and rousty Mercutio, Romeo appeared in almost pastel contrast. I would have liked to see more fire and less perfection." —Florence Fisher Parry, The Pittsburgh Press, December 14, 1934 "Basil Rathbone as Romeo made the youthful lover throb with exuberance. His lithe figure and splendid voice were always equal to the part, whose only flaw was rather too much resemblance to Hamlet." —Augustus Bridle, The Toronto Star, December 18, 1934

On December 20, the play opened in New York City. Katharine Cornell had originally planned a limited engagement of four and a half weeks at the Martin Beck Theatre, But Romeo and Juliet was so popular, it was held over until February 23, 1935. People who attended the premiere of Romeo and Juliet at the Martin Beck included: Katharine Hepburn, Lawrence Tibbett, Jane Wyatt, Walter Connolly, Nedda Harrigan, Ilka Chase, Rex O'Malley, Alexander Woollcott, Gladys Hanson, Charles L. Wagner, Owen Davis, Edward Emery, Gale Sondergaard, Herbert J. Biberman, Martin Beck, Max Gordon, Fannie Hurst, Brock Pemberton, Isidore Godfrey, Mrs. Martin Green, George S. Kaufman, Leland Hayward, George Jean Nathan and Robert Benchley. In an interview, Katharine Cornell described Romeo and Juliet as "the best melodrama in the world—swell theater. It is full of words, beautiful words—but there is a surge, a movement underneath that makes it something for the public to get excited over. We have tried to give it pace, tempo—and without slurring dialogue or situations." In a January 1935 interview with her hometown paper, the Buffalo Courier Express, Katharine Cornell told the reporter that she learned a lot about how to play Juliet from the tour last season. "At the end of that time I knew Juliet better and I knew what I wanted to do with her. So we scrapped that production. And this one, a better one, I'm sure, is the result. We recast many of the parts. And we revised the script. We have added a great deal more of the original Shakespeare. Until now we have the most complete Romeo and Juliet that has been seen in decades." —Buffalo Courier Express, January 13, 1935 Cornell also had new scenery created for the Broadway production, rather than using the scenery from the tour. She even had a new balcony built for the New York opening because the balcony used during the out-of-town tryouts proved to be unsatisfactory. "So on opening night Basil and I had to play on a balcony that we had never seen before except as a sketch. ... There had been no time for a routine rehearsal for change of set." (Katharine Cornell, I Wanted to Be an Actress, 1938) Romeo was Rathbone's favorite character to play. He played Romeo numerous times as a young man with Frank Benson's Shakespeare Company.

John Mason Brown wrote, "Basil Rathbone's Romeo is handsome; he wears his costume well, enunciates clearly and handles the verse with fluency. But though he has his moments of excellence, he is throughout much colder than one might wish, indulges in pauses which are not helpful, and speaks more slowly than is good for the production." —New York Post, December 21, 1934 Burns Mantle wrote, "a word or two of praise for Basil Rathbone, whom I did not expect to be half so good a Romeo as he is, and Brian Aherne, who I thought would be even a better Mercutio than he is. These are two fine performances, the Romeo dashing a bit suddenly into his love mood, with Rosalind still on his mind, but being beautifully sincere and impassioned thereafter. The Mercutio striking the note of banter with not too much overdoing." —New York Daily News, December 21, 1934

"Basil Rathbone is a most effective Romeo and he plays the part with admirable grace and vigor." —Rowland Field, The Brooklyn Times Union, December 21, 1934 "In reviewing an excellent Shakespearean production, like Katharine Cornell's Romeo and Juliet, there is no way for the reviewer to keep from sounding pompous and dull. If he can't find fault, there is nothing left for him to do but stroke his beard and try to think up different ways of saying 'swell.' ... I enjoyed Miss Cornell's production of Romeo and Juliet more than any other I have ever seen. In fact, for the first time I had a feeling of watching a real play. ... Basil Rathbone is not an ideal choice for Romeo, but after all, Romeo is probably not Mr. Rathbone's ideal choice for a part." —Robert Benchley, The New Yorker, December 29, 1934

"Katharine Cornell's production of Romeo and Juliet is thus far the thrilling event of the season. The high hopes that had been raised for the production were realized in the presentation the the Martin Beck. ... Miss Cornell gives what probably is the most rounded and completely captivating portrayal the present generation of theater-goers has seen. ... Unlike most stars she has not surrounded herself with a mediocre company. The nurse of Edith Evans is probably the best portrayal that has been given of the part while Basil Rathbone is a competent if not exactly a thrilling Romeo. ... The settings, which were designed by Jo Melziner, are quite the finest ever used for a production of the tragedy." —Carlton Miles, The Minneapolis Star, December 27, 1934 "The production, directed by Guthrie McClintic, is first rate. For once Shakespeare is done without the flavor of ham. ... Basil Rathbone, picturesque, with a head and profile like something by Velasquez, is the Romeo, quick, acting with slightly conventionalized Elizabethan flourishes, not quite the sweet-marrowed and effervescent mate to this ethereally wanton Juliet, a young Montague too careful to lose his handsome head and go completely lyrical over his Veronese beloved. ... You won't hear more genuine enthusiasm than expressed itself at the Martin Beck Theatre. This Romeo and Juliet is a moving and precious experience." —Arthur Pollock, The Brooklyn Eagle, December 21, 1934

Edith Evans had come from England to New York to play the role of Juliet's nurse. On January 10, 1935, Edith Evans's husband died, which made it necessary for her to return to England. Brenda Forbes filled in as the nurse until January 18, when Blanche Yurka took over the role of the nurse. Miss Yurka turned in a performance that earned praise from the critics. John Mason Brown wrote, "Capable as Miss Yurka is throughout, she rises to true magnificence in the scene in which she discovers Juliet under the influence of the Friar's drug and thinks her dead. Her cries ... are sobs that stab the heart. They are final proofs of the shading and variety which lend such vocal color and interest to Miss Yurka's characterization as a whole. And they find her at this moment outdistancing her predecessor and endowing the scene with a poignancy that even Miss Evans failed to bring to it." (New York Post, January 19, 1935) In her book Bohemian Girl: Blanche Yurka's Theatrical Life, Blanche Yurka wrote about Rathbone's performance: "Romeo and Juliet continued its New York run for several more weeks. Katharine's triumph was complete and her warm joy in it was infectious. I, for one, had been charmed and moved by Basil Rathbone's Romeo. Some of the critics had been of a different opinion, but watching it repeatedly from the wings, my first impression was, if anything, intensified. In certain scenes I thought him the best of the six Romeos I had seen. Especially in the bedroom scene his tender, muted reading was so convincing, so touching, that I never grew tired of listening to it. Some Romeos, in this scene, use sufficient voice to rouse the Capulet household a dozen times. As for the balcony scene, it is usually done in a key which would ensure the 'death, of any of my kinsmen find thee here' of which Juliet was apprehensive. Not so with Basil Rathbone. He played the whole scene in a muted voice which nevertheless carried perfectly. He was very moving, too, in the scene in Mantua, when word is brought to him of Juliet's death. "The whole performance was one which could be watched night after night with pleasure. Brian Aherne's Mercutio was brilliant both in voice and appearance. Only Katharine's desire to play a series of other parts that season prompted her to terminate the run while business was still good. I said goodbye to her and 'honey nurse' with a heavy heart."

"If a catalog of adjectives is permitted I should like to say that she is young, lovely, languorous, vivacious, fiery, virginal and wanton as she engages in her tragic encounter with Basil Rathbone's handsome and Freudian Romeo. From the Balcony to the Tomb she is a vivid and beautiful portrait. ... Mr. Rathbone's Romeo is a subject for argument. Personable in his purple tights, ardent and valiant, he is still, as my confrere, Arthur Ruhl, has hinted, not at all the sort of Romeo that Miss Cornell's Juliet would probably fall for." —Percy Hammond, The Philadelphia Inquirer, December 30, 1934 "Perhaps I'm wrong in alleging that McClintic has deliberately surrounded his wife with a bad cast—Edith Evans excepted. Perhaps he just couldn't discover a better Romeo than the stiff, unromantic chanter, Basil Rathbone." —John V. A. Weaver, Esquire magazine, March 1935 "Mr. Rathbone's Romeo is no kiddie. Because he isn't, your sympathies are with the nurse when she suggests that he stand up and act like a man. That nurse is superb in Miss Evans' hands ... So, suffice it to say, Miss Cornell's Juliet is ambitious rather than momentous." —Robert Garland, The Washington Daily News, December 31, 1934

Basil must have been discouraged by the negative critic reviews. His friend, pianist Victor Wittgenstein, wrote to him, "A true artist must know the value of his work and the sheer beauty of the Romeo which I so thoroughly enjoyed tonight was wrought by a master of his craft, an idealist and a lyricist of the highest rank. Be happy dear Basil in your achievement and be grateful that you possess that power to achieve. In my own humble way I think I know artistic beauty when I see it, and your performance was just that. Turn a deaf ear to the critics and wear the royal mantle of Romeo, which is your rightful heritage, with pride." Brian Aherne, who played Mercutio, recalled that Basil was "a fine actor ... one of the best in the profession. He was also a fine man ... good ... kind ... intelligent ... humorous ... and beloved by all who knew him." (quoted in Michael B. Druxman's book Basil Rathbone: His Life and His Films) When Romeo and Juliet closed, Rathbone returned to Hollywood and busied himself making movies, starting with Anna Karenina.

In his autobiography, Rathbone writes that he was offered the part of Murdstone in David Copperfield in July. It may have been late July or early August. According to the New York Daily News, dated August 8, 1934, Rathbone "was located by the studio's scouts on a New England farm last week." So somewhere around August 1. Rathbone also writes in his autobiography that his dog Moritz died in April. However, in the 1936 article "He Was My Friend," Rathbone wrote that when Moritz became too sick to continue with him on the tour, he left him in the care of "Miss O'D." "Two days later, 'Miss O'D' called me in New Haven and told me to come at once. I took an early morning train from Providence to New York and spent nearly three hours with my beloved friend. Then rushed back to my performance. I did not see him again. He died in his sleep that night." It seems likely that Rathbone was performing in New Haven (Connecticut) when he received the phone call about Moritz. The dates for the performances in New Haven were May 24-26. Since Rathbone wrote the article just two years after Moritz died, his memory of being in New Haven is likely accurate. (Although he may be mistaken about taking the train from Providence. Trains run from New Haven to New York. Why go to Providence?) Rathbone wrote his autobiography more than twenty years later and can be forgiven for not remembering exactly in which month Moritz died. Likewise, his memory of when he had his tonsils removed is slightly off. In his autobiography, he writes that it happened in early June. The last performance of the tour was June 20, so the tonsil surgery was likely late June or early July.

In 2003 the Martin Beck Theatre (located at

302 W. 45th St., New York City) was renamed the

Al Hirschfeld theatre after the caricaturist who spent decades sketching

theater performances. |