|

A drama in three acts adapted by Arther Hornblow, Jr., from

La Prisonnière by Edouard Bourdet. Opened at the

Empire

Theatre, New York City, September 29, 1926, and ran for 160 performances.

Produced by the Charles Frohman Company. Staged by Gilbert Miller.

|

Cast of Characters

|

Gisele de Montcel |

Ann Trevor |

|

Mlle. Marchand |

Winifred Fraser |

|

Josephine |

Minna Phillips |

|

De Montcel |

Norman Trevor |

|

Irene de Montcel |

Helen Menken |

|

Jacques Virieu |

Basil Rathbone |

|

Georges |

Arthur Lewis |

|

Françoise Meillant |

Ann Andrews |

|

D'Aiguines |

Arthur Wontner |

| |

|

|

| |

|

| Act I — Irene De Montcel's Room Act II —

The Study in Jacques Virieu's Apartment

Act III — The Study in Jacques

Virieu's Apartment The Captive is an adaptation of a French play titled

La Prisonnière by Edouard Bourdet.

It is famous for being the first stage play in the United States about a lesbian relationship—a

daring subject for a play in the 1920s! According to Basil Rathbone, Gilbert

Miller suggested that the story was based on an experience in Bourdet's own

life (In and Out of Character, p. 98). While serving in the military

during World War I, Bourdet met a fellow officer who told him of his unhappy

marriage to a lesbian. His story gave Bourdet the idea for the play. But the play isn't

only about a forbidden love; it is also about

unrequited love.

Françoise Meillant loves Jacques.

Jacques doesn't love

Françoise because he is in love with

Irene. Irene doesn't love Jacques because she loves someone else—a woman. And Irene

cannot be with the woman she loves because, in the early twentieth century,

such a relationship was considered abnormal and perverted. None of this is

made clear until the second act of the play. And for the audiences of that

era, it was the shocking twist in the love story that they never imagined.

The public loved the play, however, and it was a huge success.

|

Empire Theatre playbill |

|

|

| |

|

Helen Menken, Ann Trevor, and Basil Rathbone

photo by Vandamm

Jacques greets Irene and her little sister Gisele. |

Helen Menken, Ann Trevor, and Basil Rathbone

photo by Vandamm |

Irene and her little sister Gisele live in Paris with their father. He has

accepted a post as ambassador to Rome and plans to take his two daughters with him. But Irene refuses to move

to Rome. At first she says she wants to stay in Paris to continue her art

classes, her painting. But her father doesn't accept that excuse because Rome is

"the very cradle of art." she could easily continue her painting in Rome. He

suspects her refusal has something to do with her friends, the

D'Aiguines. Then Irene confesses that she wants to stay in Paris to be

near her friend Jacques, whom she feels is on the verge of proposing to her. M.

De Montcel reluctantly agrees that Irene can stay in Paris if she is engaged to

Jacques.

Irene then arranges a meeting with Jacques and tells him that she lied to her

father. She begs him to enter into a pretend engagement with her so that she may

remain in Paris. He suspects she wants to stay to be near another man, but

because Jacques loves Irene and would do anything for her, he agrees to the

deception.

Helen Menken and Basil Rathbone

photo by Vandamm

Irene discusses a pretend engagement with Jacques. |

Helen Menken, Norman Trevor and Basil Rathbone

photo by Vandamm

Jacques must declare his intentions. |

Act II begins one month later. Both Gisele and Irene have been allowed to

stay in Paris. Irene has continued with her "art classes" (code for meetings

with her lover, Madame

D'Aiguines). Jacques is surprised one day by a visit from Gisele, who

reports that Irene is terribly unhappy. She hopes that Jacques can do

something about it. He believes that Irene was having an affair with a man,

who broke her heart. He sends a message to M.

D'Aiguines, asking to meet him.

Meanwhile, Jacques receives a visit from Madame

Françoise Meillant, a married woman

with whom he has been having an affair. Things don't go well; she senses

that he's not interested in her anymore. They break up, and she says a

tearful goodbye.

M.

D'Aiguines meets Jacques at his apartment. Jacques confronts him about his

relationship with Irene. At first D'Aiguines says he's never been more than

an acquaintance to Irene, and he denies knowing who her lover is. When he

realizes that Jacques loves Irene, D'Aiguines warns him to forget about her:

"Leave her alone! Don't meddle in this, believe me! And don't ask me

anything more!" Jacques persists and finally D'Aiguines admits that Irene's

lover is a woman. He explains, "If she had a [male] lover I'd say to you:

Patience, my boy, patience and courage. Your cause isn't lost. No man lasts

forever in a woman's life. You love her and she'll come back to you if you

know how to wait. But in this case I say: Don't wait! There's no use. She'll

never return." He pleads with Jacques to not make the mistake that he did.

The woman Irene loves is, in fact D'Aiguines's wife, and he is miserable in

his marriage.

That same afternoon Irene drops by Jacques' apartment. She begs him to

help her: "I need someone to watch me, to hold me back. Some one who has

understood or guessed certain things—that

I can't talk about, that I can never tell!" She says that because he loves

her, he is the only one who can save her from her wretchedness. She is

struggling to stay away from the woman who captivates her. She tells Jacques

that if he will let her stay, she will give him everything a man can expect

from the woman he loves. She even believes that she will learn to love him.

"Take me in your arms. I am yours, Jacques, all of me ..." she declared.

Basil Rathbone and Ann Trevor

photo by Vandamm

Gisele: "For Irene to cry means that something is really wrong." |

Basil Rathbone and Ann Andrews

photo by Vandamm

Françoise : "And you still love her,

is that it?" |

Arthur Wontner and Basil Rathbone

photo by Vandamm

Jacques: "You're lying so as not to betray the secret of someone who is

probably your friend." |

Basil Rathbone and Helen Menken

photo by Vandamm

Irene: "It's like a prison to which I must

return captive, despite myself." |

In spite of D'Aiguines's warning, Jacques marries Irene, and Irene

promises to never again see Madame D'Aiguines. Act III opens a year after

their marriage. Jacques and Irene have been traveling and have been back in Paris

only a month. She has tried to make Jacques happy, but he knows she doesn't

love him. He says to her, "If you knew how hard it's been to convince myself

of it. The stupidly hopeful stages I went through! I've clung desperately to

the substitutes of love—from

tenderness and friendship to the most pathetic of all—compliance.

On a word or a gesture that I could interpret in terms of my desire I'd

regain confidence. Those illusions are gone. I know that I can really mean

nothing to you. I'm as incapable of making you happy as of making you

unhappy."

To fulfill his need for love, Jacques renews his affair with Françoise.

And Irene has tried to stay away from Madame D'Aiguines, but after running

into her at the studio, she is again captivated by her. Jacques sees the

light in Irene's eyes and knows that he cannot hold her. When a bouquet of

violets are delivered to Irene, she grabs her coat and goes out. The play

ends with Jacques also going out, presumably to see Françoise.

| Irene de Montcel, ordered by her diplomatist father to be prepared

to move from Paris to Brussels, refuses to go. De Montcel, suspecting Irene is

held by the fascination a degenerate woman companion exerts for her, insists

upon her going. To escape submission Irene begs a girlhood sweetheart, Jacques Virieu, to marry her. Jacques, though warned by the husband of the degenerate

that such a marriage cannot be successful, agrees to Irene's proposal.

A year later they are returned from their honeymoon. Their marriage

has been a failure and Irene, still under the influence of her friend,

deserts her husband. —The Best Plays of 1926-27, ed. by

Burns Mantle (Dodd, Mead and Co., 1927), page 390 |

Rathbone has quite a bit to say about The Captive in his autobiography

In and Out of Character. He wrote, "The play was produced without any preproduction

publicity with Helen Menken as Irene and myself as Jacques. Of course there were

rumors as to what it was all about since a limited number of Americans had seen

the play in Paris, but our first night audience was completely ignorant of its

theme. They were stunned by its power and the persuasiveness of its argument. We

were an immediate success and for seventeen weeks we played to standing room

only at every performance. At no time was it ever suggested that we were

salacious or sordid or seeking sensation" (pp 101-102).

Basil Rathbone and Helen Menken

photo by Vandamm

Irene turns away when Jacques tries to kiss her. |

Basil Rathbone and Helen Menken

photo by Vandamm

Irene: "I'm late for my appointment." |

The critics praised The Captive:

| "An unprecedented play ... an absorbing play ... a study of a young woman

struggling helplessly in the toils of an abnormal erotic passion ... Bourdet has

made the venture with infinite tact and reticence." —Alexander Woollcott in the

New York World "Bourdet's excellent La Prisonniere in its extremely adroit

translation by Arthur Hornblow, Jr., is as profoundly wrought a drama of the woe

of physical passion as has come out of France since Porto Riche's Amoureuse."

—George Jean Nathan in the New York Morning Telegraph

"Bourdet has wrought a play of gigantic proportions, of compassion and

candor, and, above all, of terrific dramatic effect. Nowhere does the inexorable

pace of the heavy marching let down ... From the moment that the sullen mystery

is invoked until it lands its ultimate smash, the play proceeds with adroit

balance and cunning. ... Adapted sensitively by Arthur Hornblow, Jr. ... The

movement is intense, swift and perpetually provocative." —John Anderson in the

New York Evening Post

|

Rathbone continues, "We were helping to educate the public to a better

understanding of a social sickness that could not be ignored. Such matters

have always been the prerogative of the theater when approached seriously

and in good taste" (p. 102).

|

The most daring play of the season is "The Captive." And one of the best

written and acted in years. The most daring play of the season is "The Captive." And one of the best

written and acted in years.

Its topic has never been previous[ly] used as a theme on the American stage.

When Gilbert Miller secured the rights in Paris, where the play known as "La

Prisonniere" was something of a sensation there, other showmen were frank in

saying the subject matter was entirely too delicate or indelicate for them to

handle.

"The Captive" is a homosexual story, and in this instance the abnormal sex

attraction of one woman for another. "Ladies" of this character are commonly

referred to as Lesbians. Greenwich Village is full of them, but it is not a

matter for household discussion or even mention. There are millions of women,

sedate in nature, who never heard of a Lesbian, much less believing that such

people exist. And many men, too.

The adaptation is such an excellent work that the unfolding of the play is

not repellent; in fact, one feels sorry for "the captive."

Arthur Hornblow, Jr., who adapted the play, just leaped into prominence among

the literati by his brilliant effort. He comes by writing naturally. He has

written of the theatre as a publicist, once for the Frohman office, by the way,

and his father has long been a commentator of plays. Young Mr. Hornblow might

well have been led upon the stage with Gilbert Miller and the players after the

second act. He probably dodged that, but his actress-wife, Juliette Crosby, who

sat out front, must have gotten a great kick out of it all.

An Austrian woman, married to a Frenchman, has lured the daughter of a

diplomat into illicit relations, but the woman does not appear on the stage. The

father suspects his daughter, Irene, of leading a suspicious existence. She

refuses to go to Rome, where he is assigned, and in answer to a barrage of

questions weaves the fable of love for a distant relation, Jacques, whom she

might some day marry. To Jacques she confesses the lie, but he had always loved

her and never understood why she has suddenly turned away from him.

Jacques stands for the story in front of her father, and he marries her, that

after a splendid scene in which the husband of the other woman tells of the

relations of his wife with Irene. The man is greyed beyond his years. When he

learns of Jacques' love for Irene he tells him to go far away until his feelings

change; that if he marries her he will be forever chasing a phantom.

A year elapses. Irene as the wife will not do. In an earlier excellent scene

she had confessed being a prisoner's captive to a desire she did not want to

pursue. She rushed into marriage in the hope of eliminating that desire forever.

But within the twelvemonth the life of the newlyweds has become platonic.

Jacques is for resuming an old affair. Irene has seen the other woman.

In anger Jacques declares she no longer means anything to him, and in the

end, caressing the violets sent by the girl friend and a symbol of Lesbianism,

they say, she goes off to her.

The case of a married woman leaving her husband for another woman is recorded

in Kraft Ebbing's book, "Psychopathia Sexualis." There are other recorded

instances.

Helen Menken, at last in light, and Basil Rathbone are the featured players

and are the Irene and Jacques of the play. Miss Menken is a remarkable person, a

young thoroughbred of the stage born. It was her fine performance that kept

"Seventh Heaven" on Broadway for nearly two years. As "The Captive," the pallor

of her make-up was somewhat distracting, but she etched the character of

abnormality, she evoked pity, she arose to the heights of pathos and her playing

cannot but command stardom from now on.

Mr. Rathbone is a rattling good actor, and he has always commanded attention.

On the opening night he was exasperating because of an almost continuously low

pitched voice. That appears not to have been his fault. Mr. Miller is reported

to have insisted on that point. The manager's idea was not to overdo the idea.

As it came out it was underdone for those three-quarters way back on the lower

floor.

Close to the shoulders of the two leads was Arthur Wonter, a well-known

English actor, new to this side. He was the husband of the other woman. His

expose of his position in his home, the lure with which she somehow still held

him and his passionate warning to Jacques won an honest and earnest tribute.

Norman Trevor, featured and starred heretofore, is content to play a

comparatively small part, that of Irene's father. He is on the stage only in the

first act, and then for a few minutes. Ann Trevor, said to be no relation, plays

Irene's sister, quite a flapper and real enough but quite indistinct.

The premiere ran until past 11.20, with the curtain rising nearly on

scheduled time. Because the crowd of notables tarried in the lobby between acts,

some minutes might have been lost. Yet so interesting in "The Captive" that it

will not lose patrons any more than it did the first performance.

"The Captive," despite the soft pedal on the players, is to be regarded as a

feather in Gilbert Miller's directional cap, and its settings are beyond

criticism. His late father would have been proud of his son for this neat bit of

work.

Of course, men will want to see this show and women will flock to it, whether

they believe it or not. It is something new for those who never heard of the

topic and naturally feminine curiosity will be aroused. Maybe "The Captive" will

never go on the road very far, but it's set for Broadway.

With the proviso that if it's not interfered with—and

a question: What is the stage coming or going to?

There isn't much left to show or talk of in a public performance after this.

And the censors!

What a play to promote censorship!

And what a play! Ibes.

—Variety, October 6, 1926,

p. 80

|

Variety reported that in its first week, The Captive grossed $14,000.

By November 10, the seventh week, Variety reported, "Capacity all performances; continuance of

abnormal demand questioned in ticket circles but on form exceptional drama

should make real run of it; nine performances, over $24,000 last week." (Nov.

10, 1926, p. 37.) The play was making a profit of more than $5,000 each week.

Arthur Wontner later played Sherlock Holmes in films from 1931 to 1937. This

play is the only time that Wontner and Rathbone worked together.

At the time she appeared in The Captive, Helen Menken was married to Humphrey Bogart (May 20, 1926 to Nov.

18, 1927).

J. Brooks Atkinson's review of The Captive was published in the New

York Times

September 30, 1926. Read the review on The Baz!

Basil Rathbone and Arthur Wontner

photo by Vandamm

D'Aiguines: "It's not only a man who may be

dangerous to a woman. In some cases it can be another woman." |

Basil Rathbone and Ann Andrews (Françoise)

photo by Vandamm |

Basil Rathbone and Arthur Wontner

photo by Vandamm

(similar to the above photo, yet slightly different) |

Helen Menken and Basil Rathbone

photo by Vandamm |

| In the play Irene's lover gave her a bouquet of violets. The giving of violets

as a symbol of lesbian love existed prior to the presentation of The Captive,

but the general public may not have been aware of it before seeing the play. The

popularity of The Captive educated the public about this symbol. Audience

members who wished to show solidarity for the characters in the play pinned

violets to their clothing. In the 1920s, however, most people were opposed to

expressing any support for homosexuality. As a result, sales of violets

plummeted

(reported in Variety , Jan. 12, 1927, p. 33). |

|

.

| M. Bourdet has described his people as ordinary

well-bred human beings, whatever their failings may be. Irene's

tenderness towards her little sister, and her own humility and

anguish, reveal her as a young lady of fine instincts; she is in no

sense the neurotic debauchee of tawdry melodrama. Jacques Virieu,

likewise, is a young man of high impulses; and of sufficient strength

of character to fly recklessly in the face of danger to support an

ideal. ... M. Bourdet does not excuse his characters on the score of

congenital weakness or worldly disillusionment or pseudo-scientific

buncombe. No, indeed, he is not interested in excuses; his is a

tragedy of consequences. He shows Irene estranged from her father,

playing false to her ingenuous sister, and fast losing all the friends

with whom she once associated freely. He tortures her before Jacques.

Once she was his ideal, a woman to whom he looked up; now she comes as

a petitioner for mercy and pity rather than respect. ... And if any

proof were needed of the sincerity of M. Bourdet's purpose, his

treatment of Madame d'Aiguines [Irene's lover] would be sufficient.

The talk of her occasionally, but by keeping her in the background and

by describing the blighted fruits of her influence, M. Bourdet retains

the fine objectivity and austerity of his drama. —J.

Brooks Atkinson, from the Introduction to The Captive, by

Edouard Bourdet |

In spite of the popularity of The Captive, some people were offended

by the subject matter. As a result, a citizens' play jury was

formed to investigate the play. The job of the citizens' play jury was to review

plays which were reported as being objectionable or salacious. If the jury voted

against a play, it could be forced to close. Variety reported that one

juror gave his opinion that not only was "The Captive" an admirable stage work

but that it was informative." (Variety,

November 10, 1926, p. 35)

On November 15, the play jury voted on the fate of The Captive. Nine

of the twelve jurors would need to vote against the play to condemn it. Six

voted against it, five in favor, and one abstained.

Arthur Hornblow (the translator of the play) said, "This is a rather critical case for the theatre. It will test whether adult subjects may be treated hereafter in a decent way on the stage." (New

York Times,

November 16, 1926, p. 23)

And so, the cast of The Captive continued to perform before

standing-room-only crowds until February 1927.

Arthur Wontner and Basil Rathbone

photo by Vandamm |

Basil Rathbone and Ann Andrews

photo by Vandamm |

.

| POLICE READY TO RAID THEATRES WITH 'DIRT' PLAYS District Attorney Banton and Police Commissioner McLaughlin came forth with

statements late last week to the effect that presentation of dirt plays would

bring about arrests and prosecutions. ... The governor again made it plain that

he did not believe in stage censorship, saying it would not work. His attitude

about fixes the status of censorship bills now pending at Albany. He even called

attention to a supreme court decision wherein it was held that any play tending

to incite or arouse impure imagination, constitutes the maintenance of a public

nuisance, is punishable under the law, even though there be no indecent language

or obscene exposure. ...

The district attorney was plain in his position stating he would make arrests

upon the complaint of any reputable citizen and prosecute under the existing

laws.

—Variety,

February 9, 1927, p. 34 |

Eighteen

weeks after opening night of The Captive, a local politician decided to make a point and close down three "immoral"

plays running on Broadway at the time, and that resulted in the

arrest of the cast of The Captive on a morals charge. The other two plays

involved were Sex (a story of a prostitute's revenge upon a society mother who

had sent her to jail) and The Virgin Man (a story of an innocent youth from

Yale beset with temptation in New York).

The night of the arrest (February 9) Rathbone went to the Empire Theatre as usual.

In his book In and Out of Character, Rathbone wrote that, looking out his dressing room

window, he saw "an unusual number of people outside and more policemen

than I had ever seen anywhere at one time in New York. . . . As we walked

out onto the stage to await our first entrances we were stopped by a

plainclothes policeman who showed his badge and said, 'Please don't let it

disturb your performance tonight but consider yourself under arrest!' At the

close of the play the cast were all ordered to dress and stand by to be escorted

in police cars to a night court" (p. 103). The cast was released on bail and

ordered to appear in court a few days later.

Basil Rathbone and Helen Menken

photo by Vandamm |

Ann Andrews and Basil Rathbone

photo by Vandamm |

Rathbone wrote that after being released on bail, the cast was forbidden

to reenter the Empire Theatre (p. 104). But he must have been remembering

incorrectly. Newspaper reports contradict that statement. The cast members

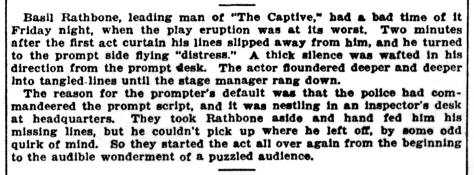

were arrested on Wednesday, February 9. According to Variety, Basil Rathbone

experienced this bad night on Friday:

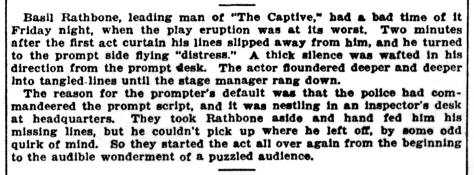

Basil Rathbone, leading man of "The Captive," had a

bad time of it Friday night, when the play eruption was at its worst.

Two minutes after the first act curtain his lines slipped away from

him and he turned to the prompt side flying "distress." A thick

silence was wafted in his direction from the prompt desk. The actor

floundered deeper and deeper into tangled lines until the stage

manager rang down. Basil Rathbone, leading man of "The Captive," had a

bad time of it Friday night, when the play eruption was at its worst.

Two minutes after the first act curtain his lines slipped away from

him and he turned to the prompt side flying "distress." A thick

silence was wafted in his direction from the prompt desk. The actor

floundered deeper and deeper into tangled lines until the stage

manager rang down.The reason for the prompter's default was that

the police had commandeered the prompt script, and it was nestling in

an inspector's desk at headquarters. They took Rathbone aside and fed

him his missing lines, but he couldn't pick up where he left off, by

some odd quirk of mind. So they started the act all over again

from the beginning to the audible wonderment of a puzzled audience.

—Variety,

February 16, 1927, p. 39 |

Because this item was reported in the February 16 edition of Variety,

it seems the reference to Friday must be to Friday, February 11. And this

suggests that the cast members were allowed to continue performing the play

until the decision was made the following Tuesday (February 15) to close the

play. The New York Times confirms this. The headline of the

February 11 edition reads:

RAIDED SHOWS STAY OPEN; INJUNCTIONS STOP POLICE

"The Captive," "Sex" and "The Virgin Man," the producers and casts of which were arrested Wednesday night, were performed last night under the protection of Supreme Court injunctions.

Basil Rathbone and Ann Andrews

photo by Vandamm |

Basil Rathbone and Helen Menken

photo by Vandamm |

The district attorney was determined to prosecute those implicated in the production of

The Captive in spite of the fact that they had been acquitted by a play jury in November. At the court hearing the management of the play announced its voluntary withdrawal from the stage in exchange for charges against the cast being dropped. The cast had no choice but to accept this decision. Rathbone felt that the closing of the play

was a "hideous betrayal, this most infamous example of the imposition of political censorship on a democratic society ever known in the history of responsible creative theater; this cold-blooded unscrupulous sabotage of an important contemporary work of art; this cheap political expedient to gain votes

by humiliating and despoiling the right of public opinion to express itself and act upon its considered judgment as respected and respectable citizens" (In and Out of Character, p.

105).

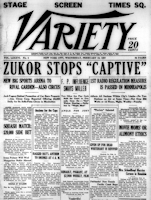

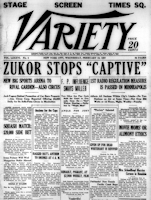

| ZUKOR STOPS "CAPTIVE" Following the raiding of three Broadway theatres—Empire, Princess and

Daly's—where the police arrested managers and actors in "The Captive," "The

Virgin Man" and "Sex," a dramatic anti-climax came on Tuesday when it was stated

"The Captive" would be withdrawn after last night's performance.

Pressure from Famous Players is understood to have caused the move. The show was

produced by the Charles Frohman, Inc., owned by F.P. and , while the managing

director is Gilbert Miller, who really presented "The Captive," Miller is

actually an employee of F.P. Miller refused to comment on the withdrawal.

On the inside it was stated the withdrawal is by "mutual consent," but it was

plainly inferred that the play might later be presented, if not by the Frohman

office, some other management. That may not occur, however, until the status of

the play is established in court. Eminent counsel has been engaged and the case

will be fought out. The show has been a big money maker, grossing between

$21,000 and $23,000 weekly.

—Variety,

February 16, 1927, pp. 1, 40 |

Download the full article (PDF file) here.

|

|

.

In a bizarre bit of irony, on the eve of his arrest for presenting The Captive, Gilbert Miller received the

Legion of Honor decoration from the French Government. Variety

reported, "The

decoration is in recognition of Miller's efforts on behalf of French dramatic

literature in America."

(Variety, February 16, 1927, p. 40) The Captive was, of course, the French

literature that Miller was promoting in America.

Oddly enough, New York Supreme Court Justice Jeremiah A. Mahoney upheld the literary

quality of The Captive, but maintained that it was immoral.

Horace B. Liveright bought the rights to the play and subsequently appealed

to the New York Supreme Court to grant an injunction to prevent the District

Attorney from interfering with his efforts to produce it.

Justice Mahoney refused to grant the injunction.

The New York Times

reported,

"Justice Mahoney gave the opinion that the drama had excellent literary quality and that it might not harm a mature and intelligent audience. On the other hand, he held that it might have dangerous effects on some persons in

an indiscriminate, cosmopolitan audience. . . On that ground, he held that the police and the District Attorney had acted correctly in seeking to stop 'The Captive' and to prevent its revival." (The New York Times, March 9, 1927, p. 27)

The

Empire Theatre in 1922 |

Gilbert Miller, who once said that Rathbone was the best equipped actor on the English stage. |

The Captive had played for 21 weeks. But Rathbone was not unemployed for long. Soon after The Captive closed, he went into rehearsal for Love Is Like That, which opened at the Cort Theatre on April 18.

|

Withdrawal of Leading Box Office Attraction Victory for City Authorities New

York, Feb. 16, UP. — The leading lady, the manager and director, the stage

director, another actress, and one elderly actor walked out of the limelight

today among the central figures in the police raided public censored play, "The

Captive," promising they would no longer appear in

the play or try to put it on again in New York. The withdrawal of Gilbert Miller

as manager, George Mondolf, Jr., as stage director, and Helen Menken, Winifred

Fraser and Arthur Lewis meant the closing down of the show at the theater where

it has been a big box office drawing card for several months. These members

agreed not to appear again in their roles under any management — but several

others, when asked to make similar promises, held back. The closing of "The

Captive" was interpreted as the first victory of the city authorities in

their moral crusade along Broadway, but the presence in the court room of Horace Liverright, publisher and producer, who announced he was negotiating with M.

Bourdet, the Paris author, for American rights to the vehicle, was taken by some

to betoken the fact that interest In the play has not died out and that

Liverright may produce it himself. Withdrawal of Leading Box Office Attraction Victory for City Authorities New

York, Feb. 16, UP. — The leading lady, the manager and director, the stage

director, another actress, and one elderly actor walked out of the limelight

today among the central figures in the police raided public censored play, "The

Captive," promising they would no longer appear in

the play or try to put it on again in New York. The withdrawal of Gilbert Miller

as manager, George Mondolf, Jr., as stage director, and Helen Menken, Winifred

Fraser and Arthur Lewis meant the closing down of the show at the theater where

it has been a big box office drawing card for several months. These members

agreed not to appear again in their roles under any management — but several

others, when asked to make similar promises, held back. The closing of "The

Captive" was interpreted as the first victory of the city authorities in

their moral crusade along Broadway, but the presence in the court room of Horace Liverright, publisher and producer, who announced he was negotiating with M.

Bourdet, the Paris author, for American rights to the vehicle, was taken by some

to betoken the fact that interest In the play has not died out and that

Liverright may produce it himself.

—Cornell

Daily Sun, 17 Feb 1927 |

.

|